The Palestinian village of Beit Iksa lies northwest of Jerusalem, within the West Bank but outside the municipal jurisdiction of Jerusalem. Over the years, land surrounding the village and some plots of land owned by villagers were seized for the establishment of Ramot Alon, a settlement that functions as a neighborhood of East Jerusalem, and Har Shmuel, a neighborhood in the settlement of Giv’at Ze’ev. In 2010, fifty more dunams of village land were confiscated for the Tel Aviv Jerusalem railway. According to a 2007 West Bank census, some 1,900 people live in the village. Many of them are residents of Jerusalem who have Israeli identity cards.

Unlike other Palestinian villages in the area, which are surrounded by a fence separating them from Israel, the eastern side of Beit Iksa – which faces the neighborhood of Ramot – is not fenced in. It lies only several hundred meters away from the Israeli neighborhood, separated from it only by a valley. However, the village is separated from nearby Palestinian communities by an electronic fence along its northwestern side that connects to the Separation Barrier. In 2009, Ha’aretz reported that the Israeli government had decided in 2006 to leave the village on the Palestinian side of the Separation Barrier – although according to the original route of the barrier, it was set to remain on the “Israeli” side. According to the article, the reason for this decision was the fact that Beit Iksa overlooks the area of Ramot and Highway 1 and that land previously purchased by Israelis lies adjacent to the village. However, no fence was erected between Beit Iksa and Israel; instead, Israel put up the electronic fence around the northwestern part of Beit Iksa, which the security establishment has defined as “temporary”.

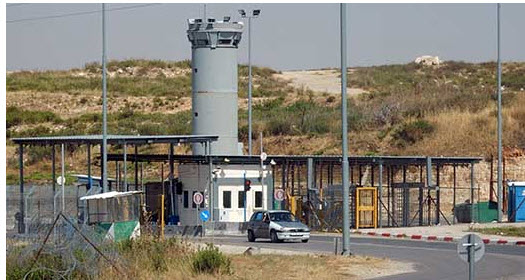

In 2008, Israel began setting up flying checkpoints on the outskirts of the village. In 2010, a permanent checkpoint was installed some four kilometers northwest of the village center, toward the neighboring Palestinian village of Bidu. The checkpoint controls the only entrance into Beit Iksa. Since then, Israeli security forces have allowed only people registered as village residents on their identity cards or bearing a special permit to enter the village. The special permits are issued upon completion of a security background check and are largely reserved for people who work regularly in the village, such as teachers and employees of the local medical clinic. The Israeli authorities also issue temporary permits in what they term “humanitarian cases”, such as family celebrations or funerals and mourning rituals, but then, too, restrict the number and age of persons allowed into the village.

In 2010, along with the installation of the permanent checkpoint at the entrance to the village, Israel also closed off the road leading from the village to Jerusalem via Ramot with a gate that remains closed. This has extended travel time from the village to Jerusalem by at least half an hour, as residents who hold Israeli identity cards now have to drive to Ramallah and from there to Qalandiya checkpoint in order to enter the city. Consequently, the villagers are cut off not only from the rest of the West Bank but also from Jerusalem, which used to be their historical center of life in the district. Since 2010, some fifty families with Israeli identity cards have left the village due to their forced isolation from Jerusalem. These families, which number some 600 people according to local council estimates, have retained their assets in the village, are still registered as its residents, and periodically come back to visit.

The severe restrictions on access to the village make it difficult for local businesses and residents to receive wares and equipment. Many suppliers are not permitted to enter the village, so clients have to go to the checkpoint to collect their goods. Some suppliers are allowed in after a process of coordination with the village council or with the Palestinian Authority, but even they are sometimes delayed at length or ultimately denied entrance. Village residents coming home with goods purchased elsewhere are also delayed at times, although there is no official restriction on bringing merchandise into the village.

According to B’Tselem, the Israeli authorities chose not to build the Separation Barrier along the Green Line in the area, instead annexing the village de facto to Jerusalem. However, they also aim to prevent Palestinians from the West Bank from entering Israel via Beit Iksa. The solution they found, to impose draconian restrictions on anyone wishing to enter the village, reflects absolute prioritization of Israeli interests over protection of the Palestinian residents’ rights.

The severe restrictions have turned Beit Iksa into an isolated community, and this isolation makes it very hard for the village residents to maintain social and family ties and to access workplaces and other services in East Jerusalem and throughout the West Bank. The restrictions also make it difficult for workers, suppliers and other service providers to enter the village, disrupting daily life there and curtailing the council’s ability to provide residents with basic services. These arbitrary, draconian restrictions deny the residents of Beit Iksa the ability to lead reasonable daily lives and cause severe harm to the entire village, according to B’Tselem.

Related: Full report by B’Tselem with testimonies of residents of Beit Iska